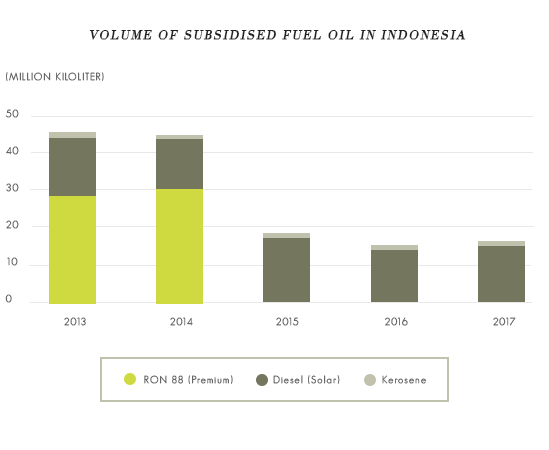

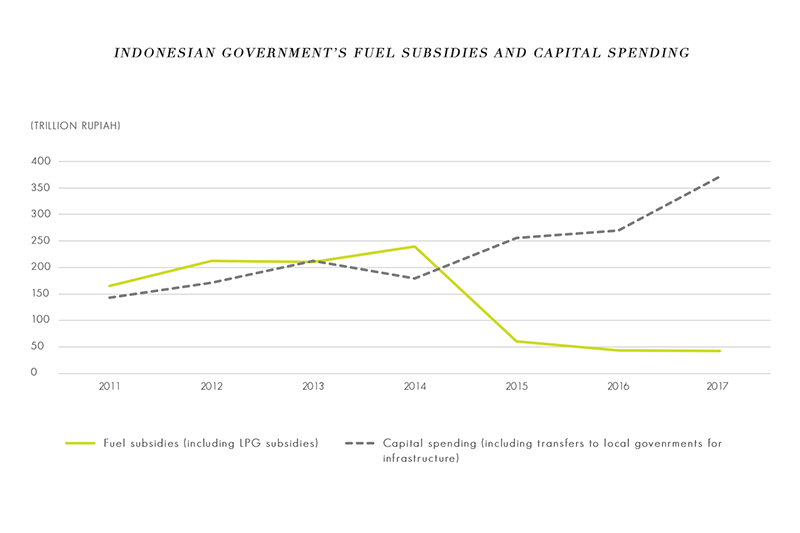

One of the Jokowi administration’s major reform policies was the discontinuation of budget transfers to subsidise RON (Research Octane Number) 88 fuel consumption in 2015. Previously, subsidies were provided to all consumers of RON 88, the then most popular type of gasoline sold in Indonesia. Maintaining this system amid high international oil prices and rising fuel consumption limited the previous government’s spending on productive physical capital, health, and education.

One of the Jokowi administration’s major reform policies was the discontinuation of budget transfers to subsidise RON (Research Octane Number) 88 fuel consumption in 2015. Previously, subsidies were provided to all consumers of RON 88, the then most popular type of gasoline sold in Indonesia. Maintaining this system amid high international oil prices and rising fuel consumption limited the previous government’s spending on productive physical capital, health, and education.

Ending the RON 88 subsidies was seen as a major step in fixing Indonesia’s poorly-targeted subsidy system.

Indonesia’s fuel subsidies were regressive because a major fraction of gasoline was used for private transport that could only be paid for by upper- and middle-class consumers. The World Bank estimates that almost 50% of fuel subsidies reached households in the richest income quintile, whereas the poorest income quintile received just around 5%.

With this reform, government spending on fuel subsidies declined dramatically. The government has used fiscal space to increase capital spending. The government has expanded investment in infrastructure projects and provided significant amounts of capital to state-owned enterprises.

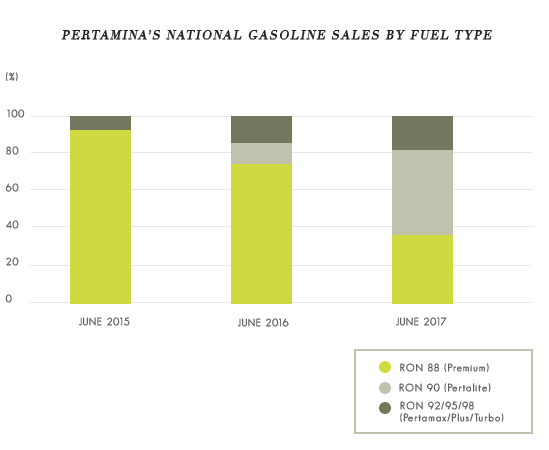

This policy has also changed consumer behaviour. As the gap between RON 88 and other higher-octane gasoline prices narrowed, consumers began to opt for higher-quality gasoline. As a result, RON 88 consumption has declined, and RON 90, which was introduced in July 2015, has become the most popular type of gasoline consumed in Indonesia.

Going back to where it began via diverse paths

Following the positive trends, some worrying signs have begun to appear.

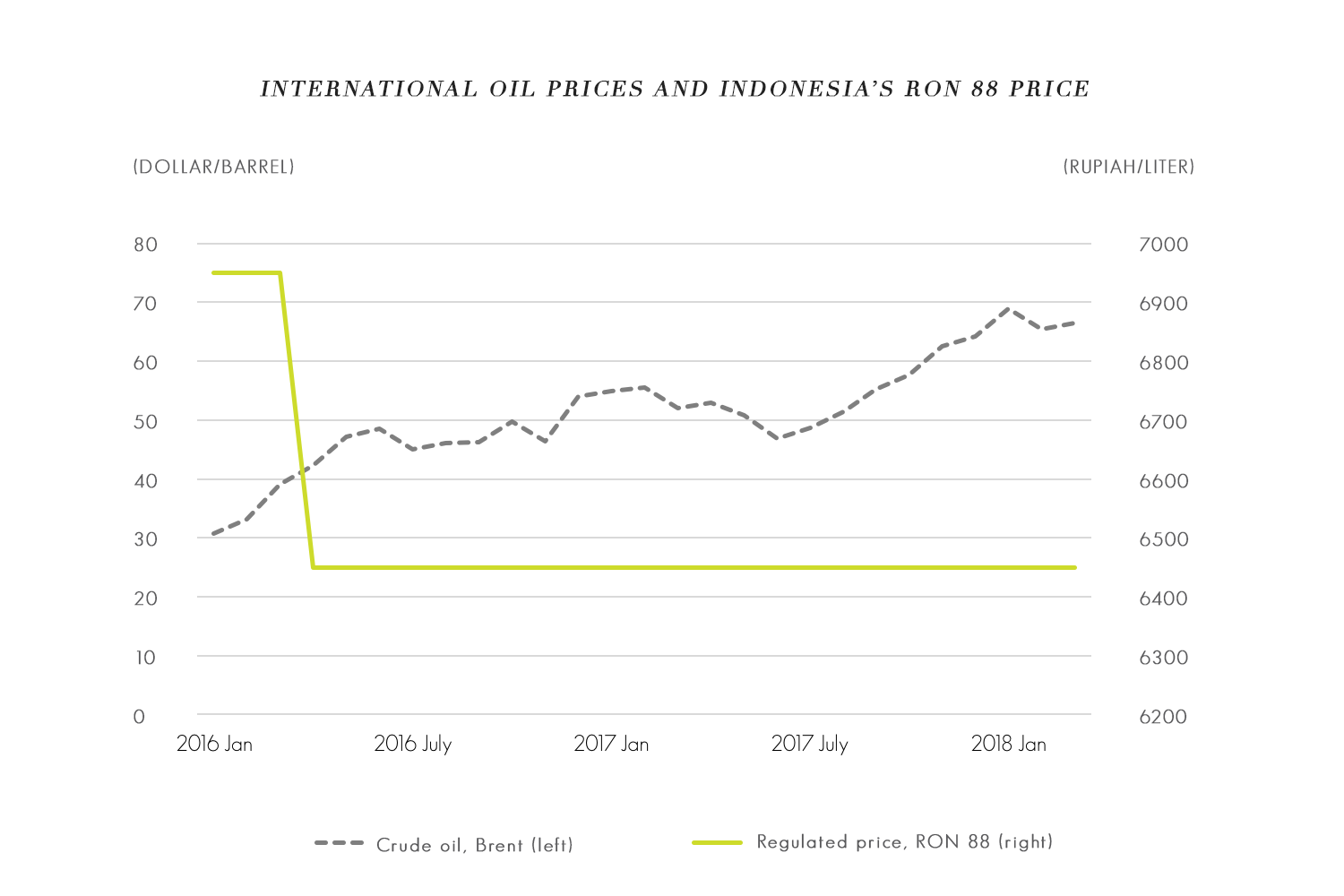

Even after the end of budgetary subsidies on RON 88, the price of RON 88 was still to be set by the government. However, the price has not been adjusted to reflect changes in international oil prices. For over two years, since April 2016, the price of RON 88 has stayed at 6,450 rupiah per liter. This price was despite the global oil price in March 2018 being 70% higher than that of two years ago. The government argues that stable gasoline prices are necessary to maintaining moderate levels of inflation.

Pertamina, a state-owned oil and gas company, is the sole supplier of RON 88. Pertamina provides implicit subsidies to RON 88 consumers when the regulated price is lower than the ‘market’ price, or the estimated level if the price were not regulated. For a significant portion of 2015 and 2017, RON 88’s market price exceeded the regulated price. The estimated fuel-sale losses for Pertamina from this disparity in prices were over 15 trillion rupiah in 2015 and 20 trillion rupiah in 2017. Escalating this concern is the government’s recent decision to maintain regulated fuel prices until the end of 2019.

After the decision to keep the regulated prices unchanged, the government was disconcerted to discover that there has been a shortage of RON 88 at filing stations. The Downstream Oil and Gas Regulatory Agency (BPH Migas) has reported that the demand for this type of gasoline outstripped supply in many regions, including Java. This issue has been cited as one of the major reasons for the government’s decision to remove the president and four other directors of Pertamina. The government is expected to take further steps to make Pertamina improve distribution of RON 88 on top of price controls.

However, RON 88 regulations are only a part of the whole policy package.

The government also intends to extend its control over non-regulated fuels. This control seems necessary as the government tries to control inflation and appease voters because RON 88 is no longer the most popular type of gasoline sold in Indonesia. Pertamina’s decision to raise fuel prices on higher-octane gasoline in February and March 2018 may have raised a red flag to the government ahead of the presidential and legislative elections of next year.

The government plans to require retailers of non-regulated gasoline, including private companies, to obtain government approval before being able to change prices. This policy, when implemented, will give little room for Pertamina to increase prices on RON 90, which has now become the most popular type of gasoline sold in the country.

Who will be left with the bill?

For now, the government does not intend to restart subsidising gasoline consumption using the budget. This policy means that, combined with high international oil prices and the government’s requirement of sustaining the supply, Pertamina is expected to incur large losses selling RON 88. As of mid-March 2018, futures markets forecast that oil prices (Brent crude) will remain high, averaging 65 dollars per barrel in 2018 and 62 dollars per barrel in 2019.

If the government is strict in approving changes on higher-octane gasoline prices, Pertamina will see its profitability weaken further as its capacity to cross-subsidise becomes limited.

These concerns are on top of the cost related to expanding the fuel supply to remote areas under the One-Fuel Price Policy that began in January 2017.

When state enterprises are burdened with the cost of carrying out public policies, the government often highlights that state enterprises’ role is not just to make profit, but also to serve the public. The government’s rhetoric makes the taxpayers think that the cost will be borne by Pertamina.

However, the deterioration of Pertamina’s financial position has a direct effect on taxpayers.

Pertamina has been the largest contributor of dividend payment to the government, accounting for approximately one-fifth of state enterprises’ totals in recent years. However, as the company’s profits shrink, so will its dividends. Lower profits will also affect the amount of tax Pertamina pays to the government.

It is expected that Pertamina’s contribution to government revenue is to weaken if the government maintains its current stance on fuel prices until the next elections. The government may partly compensate Pertamina for losses from the fuel policies. However, it is the taxpayers who will ultimately be affected by higher taxes or reduced government spending in other areas as the administration tries to keep its fiscal deficits under 3% of GDP.

Other concerns

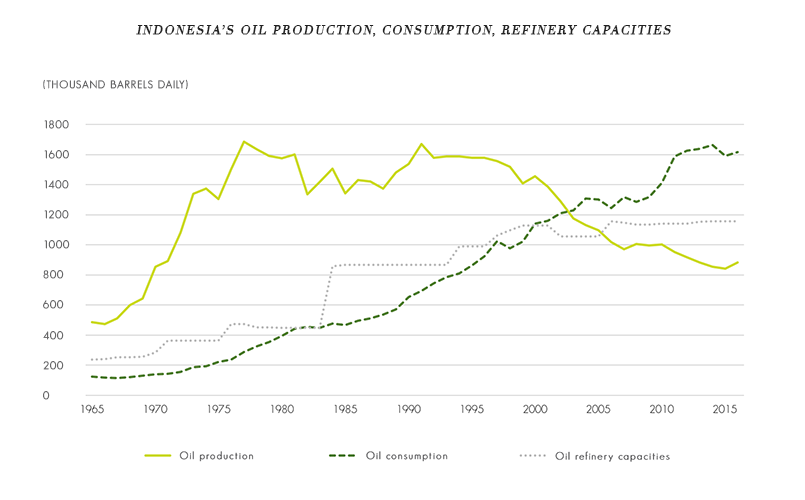

Pertamina currently faces a surmountable goal of expanding investments in upstream and downstream sectors. Pertamina has recently been instructed to take over majority stakes in eight oil and gas blocks. Further, the company plans to expand refining capacity through greenfield investments and upgrades.

The government’s gasoline price controls amid high international oil prices will provide stability for consumers in the short term but volatility for Pertamina’s operations. Business uncertainty in turn harms the company’s ability to make investments with long-term views.

Taking a wider perspective, the abovementioned short- and long-term effects on Pertamina could have negative consequences on Indonesia’s fiscal debt situation and the relationship between government ministries, which have various roles and views on the issue.

Perhaps the most irritating part for many Indonesia watchers is that the government is reviving the regressive subsidy system, which provides the majority of benefits to the upper half of the population. Indonesia’s recent fuel policies prove that the government is incapable of expanding progressive direct transfers further through targeted social assistance programs, cannot resist temptations to appease voters before the elections, or both.