I have the firmest convictions that that confidence cannot be secured by any other course than that of a frank and explicit declaration of principle; that vague and unmeaning professions of popular opinion may quiet distrust for a time, may influence this or that election but that such professions must ultimately and signally fail, if, being made, they are not adhered to, or if they are inconsistent with the honour and character of those who made them.

Sir Robert Peel, Tamworth Manifesto (1834)

After Jokowi’s victory, detailed development targets that reflected his election pledges were laid out in the National Medium Term Development Plan (RPJMN) 2015–2019. The plan included nearly 200 major targets across six areas.

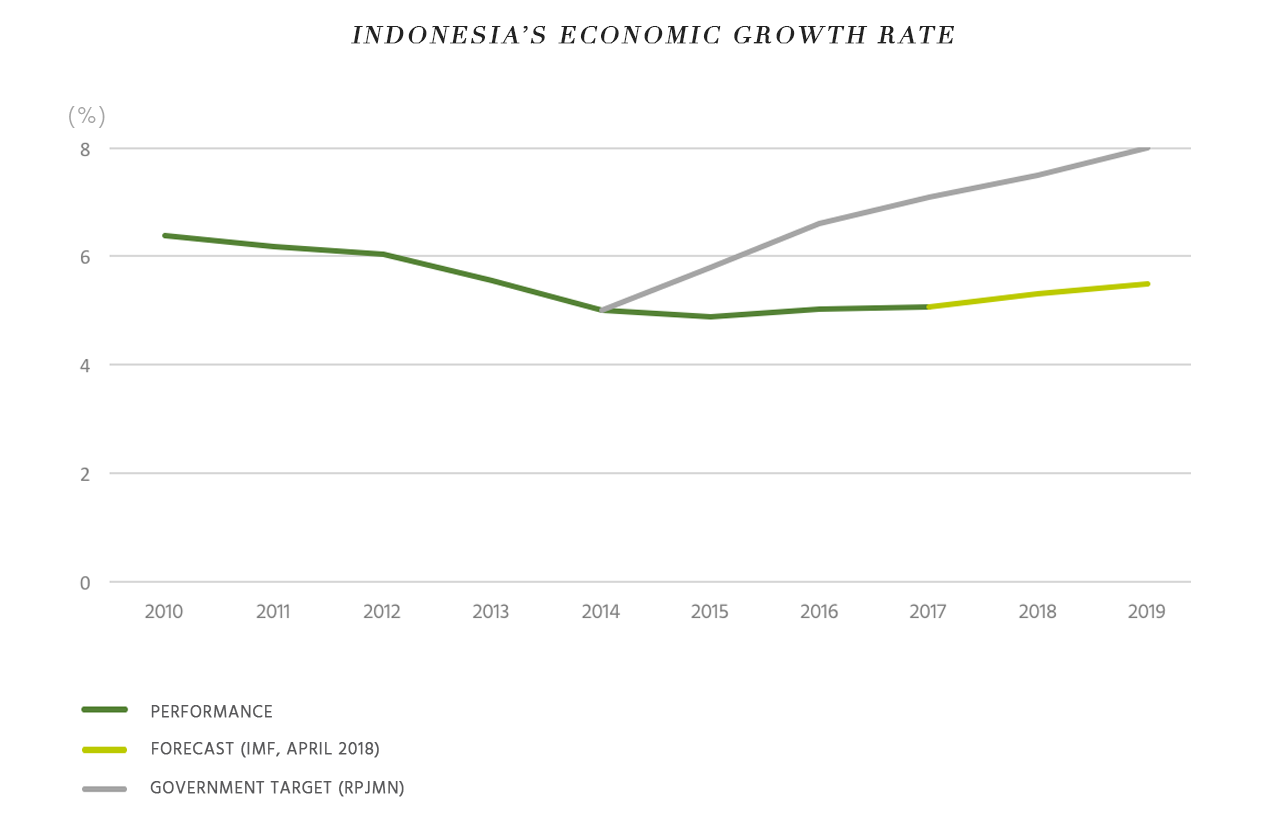

Some of the highlights were as follows: The Indonesian government aimed to accelerate the GDP growth rate from 5% in 2014 to 8% in 2019. Indonesia’s economic growth rate was aimed to average 7% per annum between 2015 and 2019. This accelerated economic growth was expected to translate into a rapid reduction in the poverty rate, from 11% in 2014 to 7–8% in 2019.

The government also stipulated its commitment to accelerating infrastructure development in RPJMN. Grand plans, such as increasing electricity generation capacity by 35 gigawatts and extending toll roads by 1,000 kilometers, were included.

Goals and gaps

With less than one year until the next presidential election, the probability of the current government achieving its major goals in RPJMN is low.

The Indonesian economy grew 5% per annum during 2015–2017, and most research institutes forecast that the GDP growth rate will remain below 6% in 2018 and 2019. As a result of this growth rate, the gap between the government’s GDP target and the IMF’s recent forecast is expected to be 9.1% of the GDP in 2019. This gap means that the size of the Indonesian economy will be 1 quadrillion rupiah (in 2010 constant prices) smaller than the government’s target.

Reaching the poverty rate goal has also proven to be challenging. If the recent trend continues, the poverty rate is expected to be 9.6% in 2019 or 1.6–2.6 percentage points higher than the government’s goal. This poverty rate means that there may be 4.2–6.9 million more Indonesian people living in poverty than the government aimed for in 2019.

Under the Jokowi administration, many infrastructure projects previously stuck in the planning stages for years have entered the construction phases. However, the implementation of these projects continues to face many challenges, and the RPJMN targets are going to be difficult to reach.

For example, the government is going to struggle to achieve the goal of increasing electricity generation capacity by 35 gigawatts. As of December 2017, just 1,041 megawatts, or 3% of the target, were in operation. If all the projects currently under construction enter operational stages by the end of 2019, the added electricity generation capacity during 2015–2019 would be around half of the goal, but even reaching this number is uncertain.

The toll road sector looks more promising, though it is still uncertain whether the target will be reached. The pace of toll road construction accelerated during the first half of the Jokowi administration, and there is currently a large stock of toll roads planned to begin operation by the end of 2019. However, it is questionable whether more than 600 kilometers of new toll roads are to become available in the next 18 months.

Other major infrastructure projects, such as the Jakarta light rail transit (LRT) and the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed rail, are also expected to miss the government’s initial deadlines.

Wishful thinking

The presidential election campaign will begin in the coming months. As candidates challenge Jokowi’s supremacy, voters will learn about the gaps between government targets and actual outcomes. These points will be low-hanging fruits for the opponents.

In this situation, it is important that voters are cautious in interpreting large gaps between goals and achievements. Voters will be disappointed to learn that many development outcomes do not meet targets, and that outcomes could have definitely been better. However, voters should also be aware that the recent performance in many areas has met or improved on the performance of past administrations.

A part of the problem is government’s overambitious goals. Most goals included in the RPJMN seemed to be a list of wishes rather than properly considered targets.

Considering the recent pattern of economic structural transformation and productivity growth, and demographic and global economic circumstances, it is difficult to imagine Indonesia’s GDP growth rate increasing by 3 percentage points in just five years. Even if economic growth had accelerated, the growth elasticity of poverty has been very low in recent years, making it difficult for the government to significantly reduce the poverty rate. These issues are challenges that are difficult to resolve in just a few years.

While infrastructure policy reform has been gradually moving forward, the actual implementation of new policies was not going to be easy, as past experience tells us. Indonesia’s infrastructure sector continues to struggle with problems related to land acquisition and financing. On top of these issues, the government’s goals have been too ambitious. The toll road construction target for 2015–2019 was 36% longer than all of the toll roads built in Indonesia since 1978 at which point the country’s first toll road came into operation. The new electricity generation capacity goal for 2015–2019 was similar to the expansion during the previous 15 years.

The cost of overambitious targets

These ambitious targets were used to win votes during the election campaign and maintain support in the early stages of the administration. As the reality began to become apparent, however, the government was advised to adjust development targets. In most cases, Jokowi was not persuaded and chose to maintain the goals. For instance, the advice of the finance minister, the energy and mineral resources minister and the National Energy Board failed to change the new electricity generation capacity target of 35 gigawatts.

There are several reasons behind Jokowi’s decision to stick to overambitious targets.

The goals were used to signal that the president wanted to break away from past traditions. Jokowi believes that these targets could make civil servants abandon the ‘old way’ of doing things and embrace the ‘mental revolution’.

Moreover, giving up the goals was going to be a major liability for a president whose political strength was weak at the beginning of his administration. Giving up the targets on infrastructure development was particularly unthinkable as Jokowi has repeatedly highlighted that his prime goal was ‘upgrading the infrastructure, fixing the infrastructure, building infrastructure.’

However, there are also costs to having overambitious goals.

The more ambitious the targets, the more complex the implementation is. Pursuing ambitious goals without appropriate coordination mechanisms could intensify conflicts between stakeholders. For example, accelerating development of certain industries could have undesirable effects on inequality and the environment. In the case of infrastructure development, each ministry is concerned with different aspects, such as the construction speed, the effects on fiscal position, and legal and procedural technicalities.

Furthermore, if the government focuses on achieving overambitious goals and prioritises speeding up the projects, product quality and workers’ safety may be jeopardised. There was a series of construction accidents early this year, and some accidents could have been prevented if the government’s aggressive drive of infrastructure development was preceded by a more thorough evaluation.

Another concern is that when the targets are deemed to be unachievable in any way in a given period of time, the goals may become meaningless. If civil servants recognise the targets as excessively optimistic promises that the president made during the election campaign, they may lose the motivation to pursue those goals.

Unrealistic goals may also hurt investment sentiment. For private investors, government priorities and project feasibility are not obvious when considering extensive lists of projects and targets. The recent cancellation of 14 of 245 national strategic projects demonstrated the risks involved in participating in the government’s ambitious programs.

Inject realism, drop rhetoric

Whoever enters the Presidential Palace in 2019, and it seems likely that it will be Jokowi again, must inject realism into the next medium-term development plan. Policy credibility, certainty, and coherence should be taken seriously rather than another flurry of megaprojects and overambitious goals.

Realistic goals can still encourage and pressure public-sector officials if the plans involve appropriate incentives and careful coordination. As time passes, voters will become aware of the emptiness of unrealistic targets, and their frustration will be a result of unfinished jobs rather than the ‘only’ modestly challenging targets. Also, the government should not forget that wise private financiers are looking for investment destinations with a trustworthy government and reliable development plans, not El Dorado.