(Originally published in East Asia Forum)

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n the wake of high-profile terrorist activities in Indonesia, social media’s role in violent extremism is once again under scrutiny. A stand-off between inmates linked to the so-called Islamic State (IS) and prison officers at Mako Brimob in early May of this year, provides some clues on how extremists use social media, especially to ‘crowdsource’.

The term ‘crowdsourced terrorism’ first emerged in 2014 and is defined as the outsourcing activity of IS for the conduct of attacks to its followers. Relevant cases include the knife attack in Leytonstone subway station in East London and the shooting in San Bernardino in the United States in December 2015. These events signaled what former US secretary of homeland security Jeh Johnson called an ‘entirely new phase in the global terrorist threat’.

Social media takes crowdsourcing – the open call for ideas, innovations and solutions as an act of contribution for a particular cause– to greater heights by allowing it to reach more people within a short amount of time regardless of geographical distance.

The Brimob inmates broadcasted the standoff through social media platforms. One inmate live-streamed a call for viewers to participate in jihad via Instagram, while showing a compatriot who had apparently died during the riot. Similar videos showed inmates pledging allegiance to IS while posing with weapons they’ve seized. The IS-affiliated Amaq News Agency also picked up the story and claimed responsibility while providing updates from the prison.

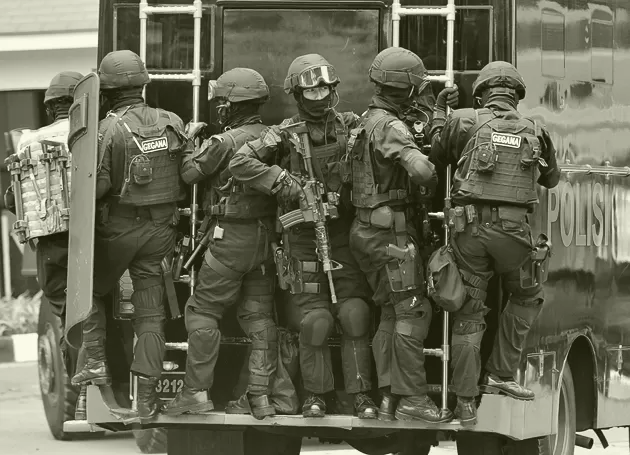

The call for participation have proved to be successful. Counterterror units were busy conducting arrests over the few days following the Mako Brimob siege. It shows the willingness of extremist sympathisers to provide manpower and material support, provided that they are aware of how they can do so. Social media enables extremist supporters to gain information on the location of and updates on a given incident through related posts and geolocation technology.

While conventional crowdsourcing employs public social media platforms, private platforms such as Telegram support the development of close social networks that are united by their investment in a specific cause.

Unlike the Mako Brimob incident, a few extremist sympathisers in Indonesia had responded to crowdsourcing in ways other than ideological agreement. Although some have acted upon their support, heading the call to travel to Syria, very few instances of locally-conducted terrorist acts could be directly linked to social media posts. The recent siege shows that under certain conditions, militants can take advantage of the platform to crowdsource personnel and material resources on national soil.

Proposed solutions to prevent extremists from exploiting social media are struggling to keep up with current events. Encryption has become a point of legal contention between tech companies and security services in several countries, including Indonesia. Intelligence agencies in the US are demanding that tech companies build backdoors to their encrypted apps that would allow authorities to monitor online communication and obtain chat transcripts.

Indonesia’s communications ministry blocked access to Telegram in July 2017 on the grounds that it was hosting extremist materials and facilitating the planning and coordination of terrorist attacks. After the terrorist attacks in Surabaya in May 2018, the ministry reported that it had removed as many as 3195 terrorist-related pieces of content on online platforms.

Technology companies have pledged to cooperate and work to remove terrorist-related content from their platforms. Telegram agreed to block the aforementioned content and to create a team of Indonesian culture and language specialists to evaluate online material more accurately. Google has also promised to step up its monitoring of terrorist content on YouTube.

The efficacy of such effort is uncertain. Technology companies typically rely on user reporting to identify extremist content, which is then relayed to human reviewers who decide whether the content violates the platform’s policies. It is a slow process and the content would have been reposted on other platforms by then.

The battle against extremism must be taken beyond social media. Reforms must start from within national legal, penal and law enforcement systems. It must also involve tackling issues such as corruption, overcrowding in prison facilities and inmate access to mobile devices.